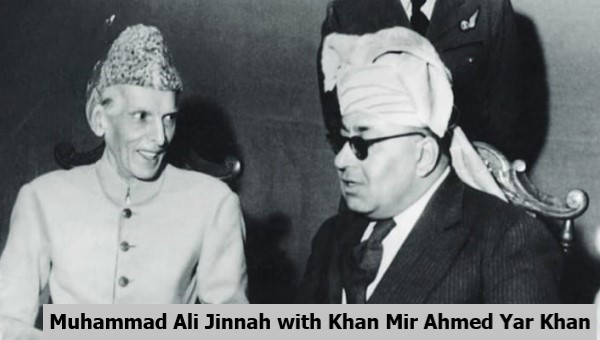

The most poignant aspect of betrayal lies in its source – it seldom originates from one’s enemies but rather emanates from those in whom trust is vested the most. This sentiment finds profound relevance when contemplating the fate of Balochistan during the partition of the Indian Subcontinent by Sir Cyril Radcliffe in 1947. The ruler of Balochistan at the time, Khan Mir Ahmed Yar Khan of Kalat, had been assured the status of an independent state by the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. However, fate had different plans.

The recent clashes between Iran and Pakistan are a consequence of conflicting interests in Balochistan, a region predominantly Shia, holding high stakes for Iran, a country of Shia faith. Conversely, Pakistan, a Sunni-majority nation, has treated Balochistan with neglect. The discontent within the local population, accumulated over the years, has manifested in the form of a struggle for freedom from Pakistan. The current political impasse traces its roots back to the post-independence days of Pakistan.

It is worthwhile to delve into the history of Balochistan, a region encompassing Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. The earliest evidence of human occupation dates back to the Paleolithic era. Settled villages emerged during the ceramic Neolithic period (c. 7000–5500 BCE). These settlements expanded during the subsequent Chalcolithic era, where the movement of finished goods, raw materials, and ceramics became commonplace. By the Bronze Age in 2500 BCE, Balochistan had become part of the Harappan cultural orbit, providing crucial resources to the expansive settlements of the Indus River basin. Pakistani Balochistan marked the westernmost extent of the Indus Valley civilization. The remnants of the earliest inhabitants were the Brahui people, a Dravidian-speaking group. The Brahuis, originally Hindus and Buddhists, were similar to the Indo-Aryan and Dravidian-speaking peoples in the rest of the subcontinent. Alexander the Great conquered the area on his way to India.

After the victory of the Mauryan Empire against the Greeks, Baluchistan came under the rule of Chandragupta Maurya. This period was a golden one in the history of Balochistan. The Arab forces invaded Balochistan in the 7th century, converting the Baloch people to Islam. Arab rule in Baluchistan helped the Baloch people develop their own semi-independent tribal systems.

Historians have shed light on the faith and religion of the Balochs from ancient times. Pottinger (1816, 1972) believes that the Baloch had Turkmen ethnic origins, while Rawlinson (1873) favors a Chaldean (Semitic) origin. Bellew (1874) aligns them with the Indian Rajput tribes, and Dames (1904) considers them from the Aryan groups of tribes. The Arab invasion of Balochistan in the 7th century took a heavy toll on Baloch ethnicity by converting them to Islam.’On August 14 and 15, while Pakistan and India were celebrating their independence from the British Empire, the princely state of Kalat (now Balochistan) gained and lost its freedom and was soon ‘forced’ into accession by Pakistan. Balochistan’s 227 days of freedom remained short-lived because of the cunning British rulers’ ploy and the betrayal by Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan.

At the dawn of India’s Independence in 1947, Balochistan was partitioned into four princely states: Kalat, Kharan, Las Bela, and Makaran. These states were presented with three options: merge with India, join Pakistan, or maintain their independence. Under the influence of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Kharan, Las Bela, and Makaran chose to become part of Pakistan.

Kalat, however, enjoyed a unique position due to the Treaty of 1876. The accord granted Kalat internal autonomy, free from British interference. It enjoyed the same status as Sikkim and Bhutan, unlike other Indian princely states. Contrastingly, other Indian states, Kalat was not a member of The Chamber of Princely States. Consequently, Khan Mir Ahmed Yar Khan, its last ruler, opted for independence.

On August 4, 1947, a meeting convened in Delhi was attended by Lord Mountbatten, India’s last viceroy, Khan of Kalat, Chief Minister of Kalat, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and Jawaharlal Nehru. In this meeting, Jinnah supported Khan of Kalat’s decision for independence. As a result, it was agreed that Kalat would be independent from August 5, 1947, and Kharan and Las Bela were instructed to merge with Kalat to form a complete Balochistan at the behest of Jinnah.

On August 11, 1947, a treaty was signed between Kalat and the Muslim League, recognizing Kalat as an independent state and promising that the Muslim League would respect Balochistan’s independence.

On August 15, 1947, the same day India gained independence, Kalat also declared its independence. The traditional flag was hoisted, and a khutbah (Islamic sermon) was read in the name of the Khan of Kalat as an independent ruler.

The Khan of Kalat expected the territories acquired by Britain through treaties in the late 19th century to be returned after 1947. Despite meetings with Mountbatten and the recognition of Kalat’s status as an independent sovereign state, the British stabbed Khan in the back by issuing a memo on September 12, stating that the Khan of Kalat was not able to undertake the international responsibilities of an independent state. It was a windfall for Khan and the people of Balochistan.

In between, much water has flowed down the Hingol (the longest river in Balochistan). In October 1947, when the Khan of Kalat visited Pakistan, he was received like the King of Balochistan by thousands of Balochs living in Karachi. However, contrary to diplomatic tradition, he was not received by the governor general or by the prime minister of Pakistan Liaqat Ali Khan— signaling a change in Pakistan’s intentions.

In his book ‘Baloch Nationalism: Its Origin and Development up to 1980’, Taj Mohammad Breseeg mentions the meeting between Jinnah and Khan, the latter was advised to expedite the merger with Pakistan.

Khan refused their demand and said, “As Baluchistan is a land of numerous tribes and the people there must be consulted in the affairs before any decision. I take, according to the common tribal convention, no decision, which can be binding upon them unless they are taken into confidence by their Khan.”

Following Jinnah’s proposal on Kalat’s merger, the Khan of Kalat summoned the legislature’s meeting, in which both houses of its Parliament not only unanimously opposed the merger proposal but also argued that it was against the spirit of the earlier agreement.

Realising the gravity of the situation, Khan instructed his commander-in-chief, Brigadier General Purves, to reorganize the forces and arrange arms and ammunition.

In December 1947, General Purves approached the Commonwealth Relations office and the Ministry of Supply in London for the supply of arms, but the British refused his demand, saying Kalat wouldn’t get any military support without the Pakistan government’s approval.

Khan also tried to rally the support of the Baloch sardars (leaders), but barring two, no one sided with him.

When Jinnah saw that Khan was only buying time, he announced the separation of Kharan, Las Bela, and Mekran regions on March 18, 1948. This left Kalat as an island, notes Dushka H Saiyid in his book ‘The Accession of Kalat: Myth And Reality’. Many Baloch sardars were willing to side with Pakistan, leaving Khan helpless.

At the same time, Khan desperately requested Indian authorities and the Afghan king Mohammad Zahir Shah for help, but with no success.

On March 26, the Pakistan Army moved into Balochistan from the coast. Khan had no option but to agree to Jinnah’s terms. Sadly, after a brief independence of 227 days, Kalat became a part of Pakistan. While signing on dotted lines, Khan, in a melancholy tone, said, signing the merger document is a “dictate of history”.

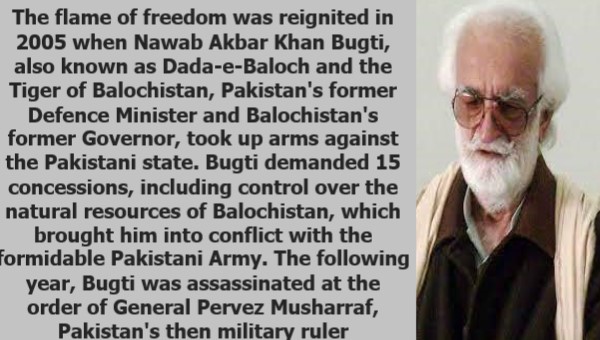

The forceful amalgamation of Kalat into Pakistan sowed the seeds of discontent and resistance, as Baloch nationalists perceived the annexation as a betrayal of their autonomy and an encroachment upon their cultural identity. In 1948, they rose in defiance under the leadership of Prince Abdul Karim, the brother of the Khan of Kalat. However, this insurgency faced suppression by the Pakistani army, and Prince Karim was subsequently arrested. Subsequent uprisings occurred in 1958, 1962, and the early 1970s, but the Pakistani state managed to quell the resistance.

Once a proud sovereign state, Balochistan now stands as the most-neglected and impoverished province of Pakistan, despite being the largest province and rich in minerals. It contributes merely four percent to Pakistan’s economy.

Recent developments have added fuel to the fire. Pakistan has granted China, its ‘Iron Brother,’ the authority to exploit resources in Balochistan. This decision resulted in numerous attacks on Chinese individuals working in the port city of Gwadar by Baloch militants.

Gwadar, connected to China’s Xinjiang province as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, has raised concerns among the Balochs. They fear that Chinese investments will bring about demographic changes in their region, transforming them into a minority group in their own province.

Despite these concerns, Pakistan adeptly manages optics. Recently, Anwarul Haq Kakar, a leader from Balochistan, assumed office as Pakistan’s caretaker prime minister, ostensibly to project him as a representative of the Balochs. However, Kakar lacks the stature of Bugti or the affiliation of a Pashtun or even a Baloch. His sole credential is his proximity to Pakistan’s influential military leadership. Even after 75 years of merging with Pakistan, Balochistan remains a neglected and impoverished part of the country.

The betrayal inflicted upon the Baloch people by Pakistan is succinctly captured in these lines: “Better to have an enemy who slaps in the face than a friend who stabs you in the back.”

See also:

Modi most significant PM after Nehru: Zakaria

Malik’s love game leaves Sania in lurch